|

AMERICAN CINEMA PAPERS

PRINT ARCHIVE PRINT ARCHIVE

2002

|

BERLIN FILM FESTIVAL – 2002

52nd INTERNATIONALE

FILMFESTSPIELE BERLIN

GRIN AND BEAR IT

by

Harlan Kennedy

What a piece of work

is a film festival. Anything can happen.

Anyone can appear, like a genie, when you least expect. (Hey, isn’t that the great Arnold

Schwarzenegger, personally opening COLLATERAL DAMAGE and smiling through

teeth as gapped, gigantic and Germanic as the Berlin Wall circa 1987?) And in

this city above all, which has belonged to every nation in turn over recent

history, or just about, reality is a moveable feast – or possibly a moveable

action spectacle.

On the night of

February 12th, 2002, World War 2 sounded as if it had broken out again. Explosions

rocked Berlin, ricocheting around the Brandenberg Gate. Thunderclaps crashed,

rumbles burst, the very clouds shook in the sky. Surreally, no actual flashes were seen, let alone - the

comforting explanation I sought on emerging from the Komische Oper after a

merry performance of THE MARRIAGE OF FIGARO (gotta get away from films

sometimes) - the rise, crackle and fountainous fall of fireworks. And few

colleagues in Berlin, when I compared notes, had even heard the noises. I was

looked at as if I were Russell Crowe in A BEAUTIFUL MIND (European-premiering

at Berlin), clinically delusional and due for attention from men in white

coats.

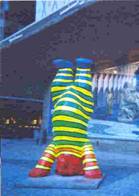

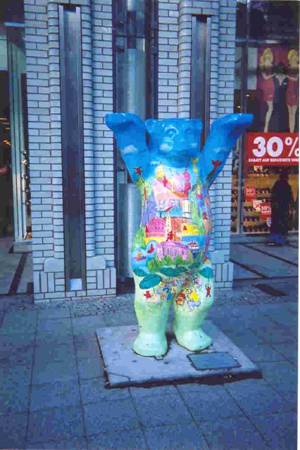

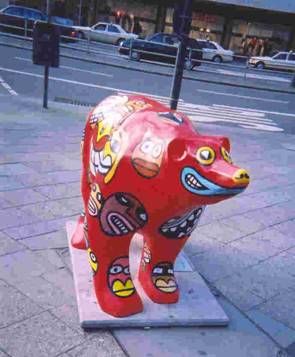

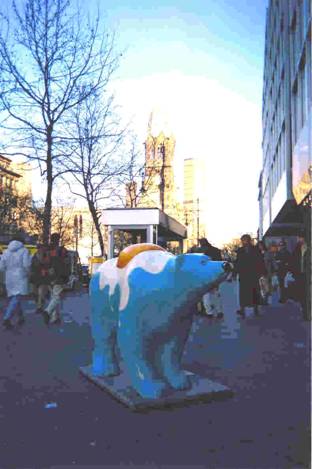

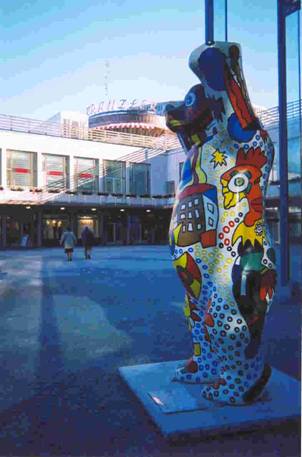

But it is a festival

critic’s vocation, one comes to learn, to notice nothing but movies. Most

didn't even notice the giant painted bears on every sidewalk, which bared

friendly teeth at pedestrians from positions standing, couchant and upside

down. And many insisted to me that the Komische Oper, with is gorgeous,

snowblinding, wedding-cake interior and glittering repertory of productions,

right here in the bustling heart of the Unter Den Linden (Berlin’s answer to

Park Avenue), had been destroyed in the war and never rebuilt.

Get the

picture? Reality doesn’t exist for

people blind or deaf to it, or tunnel-visioned to take in only the light at

the end of a projector beam. (There had

been a firework display, I learned. From a distance the cloud-cover had

obscured the rockets and razzmatazz spectacle).

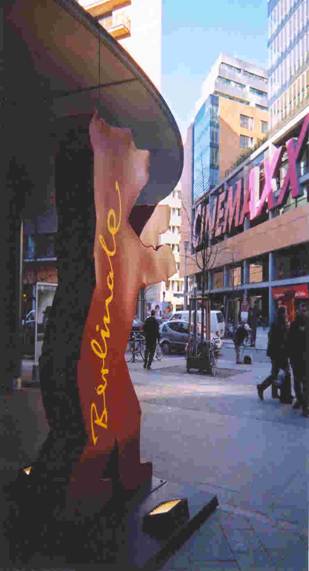

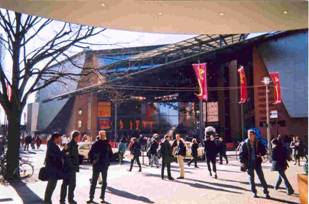

The 52nd Film

Festival performed its own triumph of delusional dramaturgy. It called itself

a makeover - "New Bears for old!" - under the fresh management of

Dieter Kosslick, replacing long-serving former festfuhrer Moritz de Hadeln.

Yet it seemed, and this is no complaint, the same majestic chaos as ever.

Celluloid spewed from every nook, cranny and fissure in the glamorous

Marlene-Dietrich-Platz, that skyscraping, many-cinema'd oasis amid a leveled,

disheveled central Berlin that still resembles a building site. (Well, it is

a building site - isn't it?)

Despite an announcement

that the filmfestspiele would for once focus on native German cinema rather

than Hollywood-led global goodies, it was non-Teutonic films that won most

attention in the feature division. From the fatherland the headline-grabbers

were yet again those Berlin-specialty fringe documentaries where the horrors

of German history are opened up like the contents of an infinitely capacious

Pandora's box.

The gemlike

nightmare this year was BLIND SPOT: HITLER'S SECRETARY, wherein the woman who

acted as Personal Assistant to the fuhrer from December 1942 to July 1945

'comes clean' from a Munich hospital bed. Interviewer-documentarists Andre

Heller and Othmar Schmiderer recorded ten hours of material, distilled to 90

minutes of mouthwatering scuttlebutt about life in Wolf's Lair, death in the

Berlin bunker (where animal-loving Hitler tried out the poison first on his

dog Blondie) and states-of-existence somewhere in between. It is hard to

credit that Nazi Germany had normal secretaries, normal typists, and normally

ambitious young girls like Fraulein Traudl Junge, who sums up her complicity

in Third Reich history with the words, "It is no excuse to be

young". No indeed. And during the festival, with a bizarrely complicit

timing, she died.

World War 2 was a

flavor of the Berlinale - when isn't it? - and three non-German movies added

their seasoning. Frenchman Bertrand Tavernier's LAISSER-PASSER (SAFE CONDUCT)

time-trips to Occupied Paris, where real-life filmfolk Jean Aurenche (Denys

Podalydes) and Jean Devaivre (Jacques Gamblin) wrote screenplays and

assistant-directed, respectively, under the suspicious eye of the Germans.

It's both funny and sobering, although at times the 3-hour duration seems

almost as long as the Occupation.

Hungary's Istvan MEPHISTO

Szabo and Greece's Costa-Gavras, of Z and MISSING, took their turns at the

antifascist coconut shy. These films were near-identical twins. Both are

English-speaking co-productions directed by far-flung Europeans. Each is

about history's attempt to Denazify a real-life German: with Szabo's TAKING

SIDES it's conductor Wilhelm Furtwangler, with Costa-Gavras's AMEN it's SS

officer Kurt Gerstein who tried to blow the whistle on the death camps. (But

the Allies wouldn't listen and the Pope was pontifically deaf). And both

films have production values worthy of a village rep pantomime. Goggle at the

painted view of St. Peter's from a Vatican Cardinal's balcony: (Costa-Gavras

throws a flock of digital birds into the air at one point, but they don't

fool us). Gape at the photo-montage backdrops of ruined Berlin, not even in

color, outside Denazification Commission officer Harvey Keitel's window.

Dramatically,

though, it's Hungary 5, Greece 1. AMEN starts auspiciously, with Ulrich Tukur

bringing emotional vibrato to Gerstein and Costa-Gavras packing the film with

clever leitmotifs, including empty cattle trains thundering meaningfully away

from the camps). But it unravels with ill-focused Vatican sequences and

hole-in-the-screen acting from actor-director Mathieu LA HAINE Kassowitz as a

conscience-stricken Jesuit go-between. TAKING SIDES has corking performances

from Keitel as the impassioned Allied interrogator set on unmasking maestro

'Willem's (as he calls him) complicity with Hitler; and from Stellan Skarsgard

as a Furtwangler by turns numinous, nervous and whitely outraged. Szabo

distils the drama to this across-the-desk face-off, which grows in subtlety

and resonance as the great questions of Art, Music, Politics and History are

invoked.

Finally there was

David Riva's MARLENE: HER OWN SONG (out-of-competition like HITLER's

SECRETARY). Dietrich's war effort for the Allies has hardly gone unsung,

mainly thanks to her own unflagging determination, when alive, to remind us

of it. But Riva, her grandson, has ransacked the archives and amateur

footage. These prove that she was at the front, that she did sing endlessly

to the troops ("Falling in a twench again....") and that she was

the west's greatest showbiz propaganda weapon. Von Ribbentrop made several

failed personal efforts to woo her back to Germany. And she risked her own

Berlin-dwelling mother's neck, though amazingly Riva has found a radio

tape-recording of the two women's first telephone conversation at war's end.

"Mutti!", "Lena!", "Mummy, you suffered for my sake.

Forgive me!"

Half way between

drama and documentary, but dragging us three decades forward to a famous

flashpoint in the Irish Troubles, was Paul Greengrass's BLOODY SUNDAY. The

day British troops fired on marchers in Derry, Northern Ireland, on 30

January 1972, killing 14, has been a marrow-spilling bone of contention ever

since. Fresh findings have discredited public inquiries exonerating the Brits

while top present-day Sinn Fein politicians have been pressured to reveal all

about the IRA's role, if any, in provoking the violence. The face-off is

vividly captured by filmmaker-documentarist Greengrass - hand-held

'you-are-there' camerawork, a lucid, lethal mapping of the trajectory of

disaster - and strongly acted by James Nesbitt as the Protestant

march-leader, MP Ivan Cooper.

Not all was war at

Berlin. Peace broke out with two wonderful movies from Japan and France,

Hayao Miyazaki's SPIRITED AWAY and Francois Ozon's EIGHT WOMEN. Oriental

animator Miyazaki made the near-legendary PRINCESS MONONOKE, where aquatint

landscapes and ass-kicking ogres mixed in a kingdom of the mind. In his new

paint'n'brush feature a little girl, parted from mum and dad in a seeming

ruined theme-park after the parents turn into pigs (Message: "Don't eat

the unattended buffet!"), stumbles into a giant, ornate, multi-storey

bathhouse frequented by gods and monsters.

Think ALICE IN

WONDERLAND gone Japanese. The film's tender but crackpot surrealism is

irresistible. How d'you like the six-armed boiler-room boss, like a human

spider working himself to a thread and modeled, Miyazaki insists, on himself.

How d'you like the ugly penthouse-dwelling Gorgon who runs the joint, with

the blue dress and coifed topknot of a fairytale Mrs Thatcher? Mainly I'd

like to take a ride on the train that goes through the sea; help bathe the

giant Stink God who turns mud to gold; or fly with the young prince who, when

it suits, becomes a whippy sky-tripping dragon-eel. Miyazaki himself is a

secret god for many western animators - from Dreamworks to Disney - but the

secret may be out after this movie gets around. Especially since it ended by

sharing the Golden Bear for Best Film with BLOODY SUNDAY.

The question 'How

many Japanese gods can you fit in a bathhouse?' prompts the follow-up question,

'How many French goddesses can you fit in a country chateau?' Francois Ozon,

of SITCOM and UNDER THE SAND, fits eight. What ever must the budget have been for HUIT FEMMES? The stellar likes of

Catherine Deneuve, Isabelle Huppert, Fanny Ardant, Emmanuelle Beart, Virginie

THE BEACH Ledoyen and the ageless, majestic Danielle Darrieux (playing

granny) ask each other 'Whodunit?' following the murder of Deneuve's husband.

The women, all connected by blood, marriage or employment (Firmine Richard as

Deneuve's black maid), enact a French-'n'-female GOSFORD PARK, though they go

one up on Altman's film by also singing songs. Each has a showstopping solo,

with Huppert and Beart vying for top honors. (The whole cast won an ensemble

Silver Bear for Individual Artistic Contribution).

Ozon surrounds his

divas with production values worthy of a high-Technicolor 1950s Hollywood

melodrama/musical/women's picture. Imagine Douglas Sirk being told that he

could have emptied the coffers of Universal. Actually, though he was swept

sideways into this makeover of a barely-known French play by Robert Thomas,

Ozon's original project was a starry French remake of THE WOMEN. May that

still eventuate.

GOSFORD PARK -

speaking of Altman's merry comeback - spearheaded an American presence no

less bristling and gleaming than usual at Berlin, despite Herr Kosslick's vow

to push back the Hollywood hordes. A BEAUTIFUL MIND, THE SHIPPING NEWS,

MONSTER'S BALL and THE ROYAL TENENBAUMS were all in contention, plus Milos

Forman's Directors Version of AMADEUS. With the movies came the stars,

including Kevin Spacey, Anjelica Huston, Oscar-shortlisted Halle Berry and

Russell Crowe. Crowe sorted out the press-conference troublemakers instantly.

At the first hint that journos were dubious about the feelgood wrap in which

Crowe and director Ron Howard enclosed and served up the story of real-life

paranoid schizophrenic and Nobel-Prizewinning mathematician John Forbes Nash,

Crowe said, "You can put your cynicism where the sun don't shine."

Actually the sun

shone everywhere this year. Even in the skyscraper-surrounded

Marlene-Dietrich-Platz lances of light picked out the guilty figures of

critics escaping, like Cary Grant from the UN Building in NORTH BY NORTHWEST,

from one of the two Korean films or four German films that had no business in

the Competition. The Golden Bear Playoff fielded a pair of total duds from

the land of the rising film industry - the Panorama and Young Filmmakers

Forum nabbed much better Korean fare - while Germany offered one hit and

several misses.

Misses included the

would-be-controversial BAADER, torpidly recreating the life and crimes of the

60s/70s radical terrorist. The film makes such a poor case for Andreas

Baader, Ulrike Meinhof and their Red Army Faction's overthrow-the-bourgeoisie

views that it could have been funded by the Christian Democrats (Germany's

closest approximation to a right-wing party). The hit was Andreas Dresen's

minor but Mike-Leighish HALBE TREPPE (GRILL POINT), about two couples falling

apart when a husband hankie-pankies with the opposite team's wife. Improvised

dialogue and Cheapocam videography contribute to something between a home

movie and a funny-tragic X-ray of the suburban German soul. Good enough to

win, and it did, the runner-up Grand Jury Prize.

The German soul: now

there's a subject to keep us up all night. Isn't it interesting that,

HITLER'S SECRETARY apart, all the Nazism-questioning movies were made by

non-Germans? Playwright Rolf Hochhuth, whose famed-in-its-day stagetext THE

REPRESENTATIVE became Costa-Gavras's AMEN, was seen - and God knows heard -

to rave to the Berlin pressfolk about the failure over three decades of any

German filmmaker to adapt his incendiary play, although (quoth Rolf)

"The rights have been out there for 28 years." Instead German news

commentators and opinionators, as well as German and non-German clerics,

railed against AMEN's poster, depicting a swastika half-shaped like a cross.

Depictions of the swastika are banned in Germany, except when used for

educational or dramatic purposes. (Like, surely, this?)

It also took a

third-generation American, Dietrich's grandson, to let light into the

long-existing mystery of Marlene's disowning of her sister. For decades, in late

life, she denied even having a sister. David Riva's aforementioned

docu-feature reveals that during the war sis and her husband ran a cinema in

the town of Belsen - yes, Belsen - to give recreation to the death camp

officers.

Of course we can't

go on forever about World War 2, even though the Berlin Film Festival

self-flagellatingly seems to want to. Was it an attempt at closure - to

liberate posterity by drawing a last line under the historical trauma - that

Kosslick screened Chaplin's THE GREAT DICTATOR as a closing gala? The

cinema's almost-first word on Hitler, made in Hollywood in 1940, still seems

worthy to be the last.

COURTESY T.P.

MOVIE NEWS

WITH THANKS TO THE AMERICAN FILM INSTITUTE FOR THEIR

CONTINUING INTEREST IN WORLD FILM.

©HARLAN KENNEDY. All rights reserved.

|

|